look out ...

Jan Křesadlo |

|

Viděl jsem ptáka |

My Cahow Sightseeing |

look out ...

| Voda v moři je neuvěřitelně modrá. Při pohledu na ni se

mi objasňuje, proč se dna a stěny plaveckých bazénů natírají či kachlíkují

právě v této barvě: Má se tím zřejmě vzbudit iluse tohoto druhu moře. Voda, jak

mně ujistil David, má však tuto barvu jaksi sama od sebe, je-li jí dost vysoká

vrstva, a to tehdy, nejsou-li v ní mikroorganismy, které by ji obarvily jinak. Pouhým zkušenostním procesem se rovněž na stáří dovídám, či chápu, proč se piráti kreslí a malují s šátkem kolem hlavy. Inu, museli si chránit temena, zajisté často též oplešalá, před jižním sluncem, ale jakýkoliv klobouk či čepičku vám na moři sfoukne ostrá bríza a přidržovat si ho často, z těch či oněch důvodů, nelze. Jako teď já se musím držet jako klíště, aby mě poskakující "Boston Whaler" neshodil se hřbetu. Řítí se, skáče, a pleskavě dopadá zpět na hladinu, jak se žene proti vlnám, dnes prý pouze nadobyčej mírným. Pomaleji to prý nejde, to by se vlny přelily přes palubu a zatopily nás. Sedět se ve člunu taky nedá: moc to stříká, a skákání člunu by vás pořádně vytřáslo, snad i poranilo. Podle instrukcí stojím, zpříma, držím se, co mohu, okraje jakési bednovité struktury, kde je kolo kormidla a rychlostní páka - jak se tomu správně říká, nevím - a péruji při každém výskoku loďky v kolenou. Klobouček mi vítr sfouknul už několikrát, naštěstí jsem ho vždycky zachytil, než uletěl do moře: v pausách, kdy jsem se nemusel držet jako klíště, jsem s ním zkoušel různé strategie a taktiky: strčit do kapsy - ale to za chvíli cítíš pálit slunce i přes chladivý vítr, zpět na hlavu - ale to zase ho bere bríza. Nakonec si ho narážím na uši na způsob vesnického debila, snad vydrží. Nejlepší ovšem by byl ten šátek - yohoho and a bottle of rum! Jízda v plochém, poskakujícím člunu má vskutku, aspoň pro mou suchozemskou českou dušičku, divoký půvab dobrodružné pirátské knížky - tohle jsem měl zažít, když mi bylo tak osm, deset let. Naštěstí mužská duše prý nikdy nedospěje, zůstává v podstatě až do smrti klukovská, a tak nyní ta moje může prožívat své Prázdniny na ostrově asi s padesátiletým zpožděním, nicméně bez újmy na vydatnosti. Chyba je jen ta, že si už nemohu dovolit hlasitě řvát a jódlovat pouhou rozkoší, protože se to jednak nesluší mému věku a postavení, jednak by takové chování bylo highly un-British, ba snad i un-American a un-Canadian. A tak tiše péruji v kolenou a řvu pouze v duchu. Má to opravdu skoro všechny ingredience příslušné klukovské literatury. Pirátská balada se tu jakoby neurčitě kombinuje se science fiction. V dálce je totiž vidět americkou vojenskou bázi, ze které se tyčí různé hypermoderní technické vymoženosti na sledování satelitů a tak: všelijaké stožáry, obrovské mísovité antény radarových přijímačů, nebo co, - to všechno v pefektním technikoloru proti kýčovitě modrému moři. Dobrodružná kniha však začasté obsahuje též učence, který buď objasňuje ostatním cestovatelům příslušné divy exotické přírody, nebo je svým geniálním intelektem bezpečně provádí nebezpečnými kosmickými příhodami - tak toho tady máme taky! |

Water in the sea is unfathomably blue. Looking at it, I see

why the floors and walls of swimming pools are painted or tiled in this particular shade:

to create the illusion of just this kind of sea. As David assures me, water gets to be

this colour all by itself, if the layer is deep enough, provided there are no

micro-organisms in it to taint it otherwise. Learning through experience in my old age I gather or grasp just why pirates get drawn and painted with headscarves on. They have to keep the southern sun off their no doubt thinning pates, but it takes more than a hat or cap to withstand the biting breeze when you can't keep holding your hand to your head for one reason and another. Like me for instance. I'm having to hold on like a leech so the jumping "Boston Whaler" won't shake me off its back. It plunges forward, leaps up and splats back to the surface as it rushes against the waves, which, I'm told, are unusually benign today. We can't go any slower, or the waves would wash overboard and flood us. Sitting in the boat isn't an option either: there's too much spray and the jumping about would shake you good and proper, cause injury even. As instructed, I stand upright, holding on as best I can to the edge of some crate-like structure housing the ship's wheel and gearstick - I'm not sure what the things are properly called - my knees cushion the springing boat. The wind has blown my little hat off several times already, fortunately I always caught it before it flew off to sea: in the breathing spaces between, I tried all sorts of strategies and tactics: stuff it in the pocket - but in no time you feel the sun blazing through the cooling wind, put it back on - but the wind snatches at it again. Finally I pull it hard down to my ears like a village idiot, and hope for the best. But a headscarf would be best - yohoho and a bottle of rum! To my diminutive Czech landlubber's soul, a ride in the flat-bottomed, bucking-bronco boat has all the wild appeal of a pirate adventure story - I should have lived this way as an eight or ten-year-old. Luckily, a man never grows up, as they say, at heart he remains boyish till the end, and so my inner self can enjoy its Treasure Island holiday fifty years belatedly, but no less intensely for all that. The only snag is that I can't afford to yell and whoop aloud with joy, it does not befit my age and status, and such behaviour would be highly un-British, no doubt just as un-American and un-Canadian. And so I silently flex my knees and yell in my heart of hearts. It really does have all the ingredients of the genre of boyhood adventure stories. The pirate sea-shanty, with a vague dash of science fiction. In the distance the American base is to be seen, and strutting from it various hypermodern technical gizmos for tracking satellites and so forth: all kinds of pylons, the giant dish antennae of radar receivers, or whatever, - all this in perfect technicolour against the kitsch blue sea. But a good Adventure story tends to have a scientist in it, either so he can expound to the other travellers the respective wonders of nature's exotica, or, by dint of his intellectual genius to see them safely through dangerous cosmic encounters - well, he's right here with us, too! |

David Wingate

| Stojí u kormidla a vypadá přesně tak, jako na těch

ilustracích. Jeho rozložitá postava páčí se na dobrých šest stop. Má ostře

řezanou učeneckou tvář, se spoustou kučeravých šedin na hlavě i na bradě -

plnovous mu ve větru tradičně povlává. Na nose má tmavé brýle, jinak jen tričko,

kraťasy, a jakési tenisky na boso - nicméně se podobá kromě učenci ze science

fiction přes tento novodobý úbor i čemusi starořeckému, mořeplavci Odyseovi,

mořskému starci Proteovi, snad i samotnému Poseidónu, bohu moře: Můj hostitel, dr. David Wingate, M.B.E. čestný DSc některé americké university, rytíž zlaté archy království nizozemského, atd., ornitholog světového jména, občanským povoláním Chief Conservation Officer na Bermudách, zaměstnanec koloniálního ministerstava zemědělství a rybářství Jejího britského Veličenstva. Stojí u kormidla, dívá se patříčně mužně a soustředěně - vous mu vlaje ve větru - a vede bezpečně naši loďku mezi neuvěřitelně modrými, bíle lemovanými vlnami. Stojím po jeho jedné straně, držím se, dle instrukcí, pevně ("you hold on like hell") kormidelnického můstku, či jak se tomu říká, a péruji v kolenou. Na druhé straně se drží a péruje Vašek, Wingatův zeť a můj kontakt se slavným přírodopiscem a touto celou snovou situací. Vysvětlujeme mu, že pérování v kolenou proti vlnám se velmi podobá pohybům při sjezdu na lyžích - a diví se zase, snad lze postřehnout i slabounký přídech závisti: David je bermudský rodák, většinu života strávil v tropickém a subtropickém pásmu, a jeho veliký sen je ornithologická výprava do Antarktidy - tak lidský duch není nikdy syt a spokojen. Vyrazili jsme zrána po snídani z ostrůvku Nonsuch, kde David zakládá živé museum bermudské přírody - snaží se uvést flóru a faunu do toho stavu, v jakém byla ještě před příchodem kolonistů. Je to přírodní reservace, a nikdo tam nemá přístup bez Wingatova svolení. Na ostrůvku stojí několik budov bývalé izolační nemocnice pro žlutou zimnici - tam sídlí David Wingate - i před školními exkurzemi apod. je chráněn tabulkou na počátku cesty k areálu bermudských nízkých palem "palmetto": PRIVATE! D.WINGATE, WARDEN. |

He stands at the helm looking just like the illustrations

make out he should, a squarely built six-foot figure, his chiselled-featured sagacious

face bordered by copious ringlets of silvery hair and beard - which flutters in the wind

as tradition directs. He besports dark tinted glasses, a polo shirt, shorts and some sort

of canvas sporty shoes on his bare feet - nevertheless, as well as resembling a science

fiction professor, and despite his modern attire, something akin to an ancient Greek, the

seafaring Odysseus, the sagacious Proteus, not forgetting Poseidon, the Sea God himself: My host, Dr. David Wingate, M.B.E. DSc honoris causa of some US university, knight of the Dutch Royal Order of the Golden Ark etc., world-renowned ornithologist, by civil occupation the Bermuda Chief Conservation Officer, and employee of the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries of this Her Britannic Majesty's dependent territory. He stands at the helm, looking suitably manly and focused - beard billowing - and guides our boat safely through the incredibly blue, white laced waves. So, I stand on one side of him, as instructed ("you hold on like hell") clinging to the helmsman's bridge, or whatchamacallit, and flex my knees. Holding and flexing on the other side is Vašek, Wingate's son-in-law and my link to this famous naturalist and this wholly dreamlike situation. We explain to him how flexing the knees against the waves is very like what you do in downhill skiing - and he expresses surprise, perhaps with a tiny hint of envy: David is Bermuda-born, having spent most of his life in the sub-tropical or tropical zone, his big dream is an ornithological excursion to Antarctica - thus is the human spirit ever yearning and unsatisfied. We set off this morning after breakfast from the island of Nonsuch, which David is shaping into a living museum of Bermuda natural history - trying to bring the flora and fauna back to the state it was in before the colonists set foot here. It is a nature reserve, off limits without Wingate's permission. On the island stand a few buildings, which were once a yellow-fever quarantine hospital - here David resides - secluded from school trips etc. by a sign at the edge of the walkway to the compound, through a grove of low Bermuda "palmetto" palms: PRIVATE! D.WINGATE, WARDEN. |

on the porch at Nonsuch house

| Tak se mi, na pozvání Davidovo, dostalo luxusu soukromého

ostrova, jaký si jinak mohou dopřát jen bermudští milionáři. Zde, na verandě bývalé zimniční nemocnice, jsem sedal, popíjeje scotch and ginger, ale s ledem, a pohlížeje snivě na modré moře, jak se bíle tříští o skaliska dalších drobných ostrůvků, nad nimiž poletují houfy bělostných ptáků faetónů s dlouhými, tenkými ocasy, které domorodci pro tyto vlastnost nazývají longtails, a kteří se obecně, pro pásmo výskytu, jmenují též tropicbirds. Viděl jsem vzácné bukače noční Nycticorax violacea, se žlutou chocholkou, hnízdit na přísně chráněných místech tohoto chráněného ostrůvku, viděl jsem ostrovní, bermudskou formu ptáčka vireo, s kratšími křídly a delšíma nohama, než má pevninová forma americká, na čemž je vidět postup vývoje druhů v činnosti, neboť mnoho ostrovních ptáků ztrácí postupně schopnost letu, nemají-li specifických nepřátel, atd. |

So then, at David's invitation, I am luxuriating on a private

island, such as only Bermuda millionaires might afford themselves. Here, on the porch of the former yellow-fever hospital I used to sit, sipping scotch and ginger on the rocks, my eyes wandering dreamily over the blue sea shattering whiteness over the rocks of the other little islands, above which thronged dazzling white phaeton birds with long thin tails, for which characteristic the locals call them Longtails, and which are generally known for reasons of their range as Tropicbirds. I used to watch the scarce Yellow-crowned Night Herons Nycticorax violacea, nesting on strictly protected portions of this protected island; I watched the insular Bermudian variety of the white-eyed vireo, whose wings are shorter and legs longer than the American mainland variety, this being practical evidence of the evolutionary selection of species, since many island birds gradually lose their ability to fly, lacking specific predators etc. |

'the old wreck'

| Plaval jsem, s maskou a v ploutvích, kolem

přístaviště na Nonsuch, kde jsou ve skále vytesaná skladiště snad od pirátů,

nyní používaná ministerstvem rybářství pro účely spojené s ochranou přírody, a

kde Wingate přivazuje svůj člun ke kostře lodního vraku, tam, kde její konec

poněkud vystupuje nad hladinu. Kolem tohoto vraku a v něm jsem plaval a potápěl se v masce s trubičkou - provozoval tzv, snorkelling - a žasl nad rozmanitostí korálů a fantastických ryb, obývajících tento umělý útes. Ale David se mému nadšení shovívavě usmál: To tady, to ještě nic není, počkej, až uvidíš The Northern Reef. Nevěřil jsem mu, dokud jsem jej neviděl - ale to už by nás odvedlo příliš daleko od zamýšleného líčení ... Nyní však jsme z ostrůvku Nonsuch vyrazili a šineme si to, jak vylíčeno, jiskřivou slání za dalšími vzrušujícími zkušenostmi. Náš cíl, abyste věděli, není jen tak něco - není na světě mnoho lidí, kterým byl tento pohled dopřán. Kromě různých vědeckých kapacit to byl například princ Filip, vévoda z Edinburgu, manžel Jejího britanského Veličenstva královny Alžběty II. - a to ve své funkci presidenta Světové federace ochrany přírody, nebo jak se to správně přesně jmenuje. Toho také odvezl Wingate na podívanou, která je hlavním důvodem jeho světového věhlasu. Vlny se valí, vítr věje, poskakujem pořád víc, až se mi, jako suchozemské kryse, začíná trochu zvedat žaludek. Podle instrukcí upírám tedy zrak k obzoru: tam se voda zdá fialová (je to tedy obráceně, než podle Máchy: blízko do zelena, čím dál, víc do modra) a lze na ní rozeznat zvláštní pěnivé hřebeny. To jsou tzv. "boilers", korálové útesy, ve kterých se točí a pění voda skutečně jako by vřela - u těch jsme byli minulý týden s jedním fotografem. Avšak náš dnešní cíl je jiný. |

I used to swim with mask and flippers around

Nonsuch dock, with its storehouse spaces carved in the rock by pirates for all I know, now

used by the Ministry of Fisheries for activities associated with nature conservation, the

dock where Wingate tethers his boat to the shell of a sunken ship, to the end part of it,

which rises a little above the water. I used to swim around and through this wreck and dived with mask and snorkel - in wonderment at the multiplicity of corals and fantastical fishes who live on this man-made reef. But David only smiled indulgently at my enthusiasm: This is nothing, wait till you see the Northern Reef. I did not believe him, until I did see - but that would take us too far off our intended narrative ... But now, having departed Nonsuch Island we are making our way as described through the sparkling saline in pursuit of new and exciting experiences. I'll have you know that our journey's aim is not just any old spectacle - there are not many on this Earth who have had the privilege to see it. Apart from various scientific authorities one could mention prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, consort to Her Britannic Majesty Queen Elizabeth II - in his capacity as the President of the World Wildlife protection Federation, or whatever it's called exactly. He too was taken by Wingate to the show which has earned him world-wide renown. The waves roll on, the wind blows, we bounce around more and more, until at last my land-rat's stomach begins to protest. I follow advice and fix my gaze on the horizon: the water seems violet there (so it is the reverse of what the Czech poet Mácha wrote: the nearer the greener, the further the more indigo) and peculiar foamy ridges are to be discerned there. These are called "boilers", coral reefs in which the water twists and foams as if it were boiling - we went to them last week along with some photographer. But today we're heading elsewhere. |

a Boiler reef

| Skalnatý ostrůvek před námi se rychle přibližuje. David

ubírá rychlost, blížíme se k pobřeží. "Až ti řeknu, vyhoď doprava kotvu,

ale ne dřív," nařizuje David Vaškovi. Člun teď, při příboji, skáče jako

pominutý - naštěstí mně chvilkový náběh na mořskou nemoc už přešel -

"now!" křičí Wingate a Vašek vyhazuje kotvu. Řetěz se s rachotem odvíjí,

a člun směřuje k rozeklanému skalisku. Wingate už vypnul motor a stojí teď na

přídi s lanem v ruce. Zkušeným zrakem pozoruje houpání vln proti břehu - teď! - s

elegancí a silou, nečekanou u sivého vousáče, vyskakuje David na břeh. Táhne,

uvazuje lano za hrotitý skalní výběžek - pak říká Vaškovi, kdy má skočit. Nakonec se dostávám na břeh i já, tentokrát bez úrazu, při poslední návštěvě před týdnem jsem upadl a ošklivě se pořezal na boku o skálu - zdá se, že si zvykám a rozhýbávám se. Vylézáme na skalnaté stráně ostrůvku: má uprostřed jezírko slané vody, které se naplňuje při přílivu, a ve kterém lze vidět veliké modré "blue parrotfish" (Scarus coeruleus, zajímá-li vás to). Vylézáme výše za cílem excurse. |

The rocky islet ahead of us quickly approaches. David

throttles back, we are nearing the shore. "When I tell you, throw the anchor to the

right, but not before," David commands Vašek. Now, in the swell, the boat lurches

like mad - I'm glad the momentary sea-sickness nausea has left me - "now!" cries

Wingate and Vašek hurls the anchor. The chain unravels raucously, and the boat heads

toward the jagged cliff. Wingate has already switched off the motor and stands on the bow

holding a towrope. He sizes up the swell rolling against the shore with his knowing eye -

now! - with elegance and strength unexpected from a greybeard David leaps ashore. He

pulls, tethers the rope by a spiky rock outcrop - then tells Vašek when to jump. Finally, I take my turn to get ashore, this time without mishap. On my last trip a week ago I fell against a rock and grazed my side badly - I seem to be getting used to things, loosening up. We clamber up the rocky scree of the little island: in the middle is a saline tidal pool, where you can see large blue parrotfish (Scarus coeruleus, if you're interested). We go higher in pursuit of our excursion's aim. |

| Téměř posvátně snímá Wingate pečlivě zakamuflované víko umělé hnízdní nory z betonu. Nakláníme se nad otvor: Je tam! Hnědošedá, chlupatá koule, asi zvící hlavy nemluvněte. Na jednom konci to má ptačí hlavu s černým, zahnutým zobákem, kterou to ihned schovává do stínu. Nicméně, i za ten okamžik vidím jasně zvláštní trubičkovité nozdry, charakteristické pro řád bouřňáků. Procellariformes. Mládě převzácného, legendárního ptáka Kahau! Ve vedlejší noře je mládě už pokročilejší: z kuřecího prachu už čouhají černobílé letku dlouhých křídel, ještě dvě další hnízda přehlíží David na tomto ostrůvku, či spíše mořském skalisku, ale tam nám s sebou nedovolí. Neřekne to ovšem takhle nebritsky naplno: pouze, že by to nedoporučoval - he would not recommend it. Cesta k těmto hnízdům je vskutku krkolomná, vysloveně horolezecká, nicméně, mořský stařec David k nim šplhá jako mladík. Co viděl, zapisuje si David levou rukou do speciálního diáře. | Almost religiously Wingate is removing the well camouflaged lid off the artificial concrete nesting burrow. We bow over the opening: There it is! A grey-brown, fluffy ball, about the size of a baby's head. At one end it has a bird's head with a black hooked beak, which it immediately hides in the shade. Even so, in that instant I clearly see the peculiar tubular nostrils, so characteristic for the petrel family, the Procellariformes. A most precious youngster, of the legendary Cahow-bird! In the neighbouring burrow the youngster is more advanced: there are black and white flight feathers poking out of the chick's down, then two more nests for David to inspect on this island, or rather this oceanic rock, but he doesn't let us follow him there. Not that he would be so un-British as to say so outright: it's just that - he would not recommend it. The way up to these nests is truly arduous, literally for rock-climbers, nevertheless the oceanic patriarch David scales up like a young'un. David jots down what he has seen with his left hand into his special notebook. |

Cahow 'government housing' inspection

| Pak odrážíme, a podobným způsobem navštěvujeme ještě

několik dalších ostrůvků, kde všechno probíhá obdobně, v podstatě stejně jako

na prvním. Nicméně, některé podrobnosti jsou nové a zajímavé. U jedné nory - přirozené, bez inspekčního odsunovacího víka - mě David upozorňuje, že mládě uvnitř je již značně pokročilé. Rodiče je již opustili, přestali krmit, a mládě tráví z tuku - proto totiž se jeví dospělé mládě mohutnější, než vypeřený pták, je tak tlusté. Co pije? Pít nemusí. Získává vodu metabolismem tuku, a dovede jí využít. V noci však vylézá před noru a cvičí si křídla až nakonec uletí na širé moře. Jak to David ví? David fouká do písku před norou. Pod jeho dechem se pohybují chmýříčka, kterých jsem si předtím nevšiml - to je prach z přepeřujícího se kuřete. Jak vylézá, zanechává prach na písku a na vegetaci. "Podle toho poznám, že v noře je mládě, které už cvičí. Taky jsou v písku stopy." David písek před norou pečlivě uhlazuje, aby mohl příště číst nové stopy. Vykládá nadšeně, jako pravý zažraný vědec ... ještě další ostrůvek a pak ještě další - a nakonec se zase vracíme na Nonsuch. Nevycházím z údivu: Nejen, že jsem na Bermudách, ale dokonce jsem viděl ptáka Kahau! Živého! V různých stádiích vývoje, od chlupatého kuřete až po téměř přepeřeného mladíka. Dospělého Kahau jsem ovšem neviděl, ale ty vídá i David jen zřídka, při inkubaci vejce, nebo náhodou. Kahauové tráví totiž celý rok na širém moři, vlastně neznámo kde, a své hnízdní nory navštěvují jen v noci. Kromě toho jsou dnes nesmírně vzácní. Ono už dostat se v životě zrovna na Bermudy je, pro normálního českého Honzu, trochu nepravděpodobné. No, ale budiž. Jenže - vidět ptáka Kahau - to je jiná! Právě před týdnem tuto milost David Wingate odmítl bohatému Američanovi, který přistál na Bermudách v rámci zábavní cesty po karibských ostrovech ve své soukromé jachtěů i když naznačoval, že se dobře zná s guvernérem, a později, že by to jako nechtěl zadarmo ... |

Then we set off, and in a similar vein visit a few more

islets, where everything happens much as on the first one. Some details, however, are new

and noteworthy. By one of the burrows, a natural one, without a removable inspection cover - David draws my attention to something. The youngster inside is quite advanced. Its parents have left it now, stopped feeding it, and the youngster is living off its fat reserves - the reason why a juvenile looks bigger than an adult feathered bird is the fat layer. And what does it drink? It doesn't need to. It gets its water by breaking down the fat, metabolising it and using the water direct. At night it comes out in front of the burrow and exercises its wings until finally it sets off to the open sea. How can David tell? David blows at the sand in front of the burrow. Little fluffy bits I never noticed were there now move under his breath - the down of the moulting chick. As the chick comes out, it leaves traces of down on the sand and vegetation "That's how I know there's an exercising juvenile inside. Look at the marks in the sand." David smoothes the sand before the burrow again carefully, so he can make out new markings next time. He enthuses like the passionate scientist he is ... another little islet and another - and finally we head back to Nonsuch. I can't quite believe my luck: Not only am I in Bermuda, but I've even seen the Cahow! Alive! In different stages of development, from a fluffy fledgling to an almost fully feathered juvenile. Not an adult stage of course, even David sees those infrequently, when they are sitting on the egg, or by pure chance. Cahows, you see, spend almost the entire year out at sea, nobody knows quite where exactly, and they visit their nesting burrows only at night. Apart from which they are incredibly rare these days. To get to Bermuda is an unlikely enough achievement for an ordinary Czech bumpkin. Very well, then. But to see a Cahow - that's something else entirely! Just last week David Wingate turned down the request to do so from a rich American, who set foot on Bermuda as part of his joyride to the Caribbean in his private yacht, even when he mentioned he was known to the Governor, and after that, that he wasn't expecting any free favours ... |

| Proč však jest tak těžké ptáka Kahau uvidět, nebo se

dovědět, kde přesně hnízdí? Protože je právě nesmírně vzácný. Když byl v

roce 1951 znovu objeven, bylo to, jako kdyby někdo zjistil, že dosud existuje Blboun

nejapný, pardón: Dodo mauritánský - moderní ornithologové bez smyslu pro

humor nám totiž blbouna zrušili. Pták Kahau, Pterodroma Cahow (Nichols & Mowbray) je bouřňák asi velikosti holuba, má však mnohem delší křídla, v rozpětí něco víc než metr. Podrobný slovní popis nemá význam. Snad jen, že je hnahoře šedočerný, s bílým čelem a trochu běli u kořene ocasu, a vespod bílý. Má krátký zahnutý zobák s typickými trubičkovitými nozdrami nahoře: tento druh nozder charakterizuje bouřňáky a souvisí s faktem, že pijí mořskou vodu a přebytečnou sůl vylučují pomocí zvláštní žlázy a pak jaksi vysmrkávají. Nohy má s plovací blánou, čtvrtý prst zakrnělý, jak je opět typické pro bouřňáky. Je to druh tzv endemický pro Bermudy, to znamená, že nikde jinde nežije. Přesněji řečeno, nežije ani vlastně na Bermudách, protože většinu času tráví neznámo kde na moři, či nad mořem, prý i spí na křídlech a svou potravu z moře loví v letu. V říjnu se za noci vrací na Bermudy, totiž dnes už jen na ty malé ostrůvky kolem Nonsuch, kde pak probíhají jeho prekopulační rituály. Tehdy se také v noci ozývá naříkavými skřeky, které mu vynesly jeho jméno Cahow či Kahau. Svatba Kahauů pokračuje po celý listopad, a pak následuje šestinedělní svatební cesta na moře. V lednu se páry vracejí a kladou v norách jediné vejce. Inkubace trvá padesát tři dní. Mládě se vyvíjí osmdesát až sto dní. V posledním období rodiče mládě opouštějí a vracejí se na moře. Mládě, vypasené do nemožnosti, tráví z tuku, v noci vylézá a cvičí křídla, až pak někdy koncem května či začátkem června ulétá rovněž na oceán. Dospělí Kahauové přilétají na pevnou zemi vždy jen v noci, proto snad se přece jen zachránili před úplným vyhubením a proto také tak dlouho unikali pozornosti vědců. |

Why then is it so difficult to get to see a Cahow, or even to

find out where to find it? Precisely because it is extremely rare. When it was

rediscovered in 1951, it was as if someone discovered that the Mauritius Dodo still lives.

[Dodo means simpleton in Portuguese. But ornithologists with no sense of humour have named

the 'dumb fool' Raphus cucullatus.] The Cahow-bird, Pterodroma Cahow (Nichols & Mowbray) is a petrel, about the size of a pigeon but with much longer wings, a wingspan of almost four feet across. There's little point in a detailed verbal description here. Suffice it to say that it is grey-black on the back, white on the forehead and a bit of white at the base of the tail, and white underneath. It has a short hooked beak with typical tubular nostrils at the top: these kind of nostrils characterise the petrels and relate to their ability to drink sea water and excrete the superfluous salt via a special gland, and then kind of snort it out. Its feet are webbed, the fourth toe vestigial, again something typical for the petrels. The species is endemic to Bermuda, which means it lives nowhere else. More precisely put, it does not live even in Bermuda, since it spends most of its time who-knows-where at sea, or above it, reportedly even sleeps on the wing and snatches its food from the surface in full flight. During October nights it returns to Bermuda, or rather nowadays to just the few rocky islets around Nonsuch, where its prenuptial rituals are conducted. During these times the night carries the plaintive shrieks which gave the bird the soundalike name Cahow. The Cahows' wedding rites continue through November, followed by a six-week honeymoon journey out to sea. In January the pairs return and lay a single egg in their burrow. It takes fifty-three days to incubate. The fledgling matures between eighty and one hundred days. In the last stages the parents leave their young and fly back out to sea. The youngster fattened beyond belief lives on its fat reserves, comes out of the burrow at night and exercises its wings, until sometime at the end of May or beginning of June it too departs to range the ocean. Adult Cahows come ashore only at night, which may be the reason why they escaped complete extinction and why they escaped the attention of the scientists for so long. |

a rare sighting of a Cahow at sea

| Historie ptáka Kahau je zvláštní a romantická, jako

celé ovzduší a historie Bermud. Když v roce 1504 španělský mořeplavec Juan de Bermudez objevil Bermudy, bylo na nich všemožných mořských ptáků sta a sta, tisíce a milióny. Nežil na nich žádný savec, a jediní čtvernožci byly původní bermudské ještěrky. Španělé Bermudy objevili a pojmenovali, ale neobsadili. Ostrovy byly nebezpečné pro přistání - kolem vlastních ostrovů, vyčnívajících nad hladinu a dnes spojených mosty v jeden dlouhý ostrovní pár, jsou všude kolem roztroušená skaliska a ponořené korálové útesy, na kterých mnoho lodí ztroskotalo. Kromě toho, v zimních měsících, děsil za noci španělské mořeplavce zvuk nesčetných křídel a naříkavé skřeky, které se tehdy musely ozývat v mnohohlasých neutuchajícíh chórech. Pro navigační bezpečnost a tajemné noční nářky byly Bermudy nazvány "Las islas del diablo", Ďáblovy ostrovy. Nicméně Diego Ramirez, který byl na Bermudy zahnán bouří r. 1603, objevil, že zdánliví ďáblové jsou ptáci, létající a ozývající se v noci. Byli to ptáci Kahau, kteří tehdy na Bermudách sídlili v miliónech. Ale již tehdy začala lidská civilizace Kahauům zvolna odzvánět. Španělé totiž vypustili na ostrovech prasata, aby měli v případě potřeby zásoby masa, a prasata vyhrabávala a žrala vejce a mláďata Kahauů. Tehdy totiž sídlili Kahauové na hlavní půdě ostrovů, kde si vyhrabávali dlouhé chodby v měkké zemi. Když v r.1609 ztroskotala u Bermud loď Sea Venture, přivážející zásoby kolonistům v Virginii, pod velením Sira George Sommerse, byli už Kahauové jen na ostrovech, kam se prasata nemohla dostat plováním přes moře. Nicméně jich bylo pořád na tisíce. Sommers obsadil Bermudy pro britskou korunu, z trosek lodi Sea Venture postavili jeho námořníci dvě malé lodice Patience a Deliverance, které nakonec hladovějícím kolonistům ve Virginii pomoc přivezly, ale Sir George na Bermudách na zpáteční cestě zemřel. Jeho tělo bylo dopraveno zpět do Anglie, jeho srdce pohřbeno na Bermudách, asi nikoliv z romantického sentimentu, ale aby se jim po cestě do vlasti i při nasolení nezkazil, pohřbili nejspíš se srdcem i jeho ostatní útroby. Ale Kahauové na kolonisaci těžce doplatili, neboť kolonisté v nich objevili vydatný zdroj potravy. Stačilo prý rozsvítit v noci na pobřeží pochodeň, a pak srážet zvědavé ptáky klackem po tisících. Když v r.1615 se dostaly z lodí na ostrovy krysy a zničily všechny zásoby, přeplavili se bermudští kolonisté na Cooper's Island, kde se živili pouze masem Kahauů. V r.1616 vydal guvernér ostrovů Daniel Tucker ostrý dektret "against the spoyle and havocke of the Cahowes", ale to už bylo pozdě. Co nezničili lidé, dodělali psi, kočky, vepři a krysy. Když se v minulém století začali osvícenější námořní důstojníci bermudské posádky zajímat, co to byl ten Kahau, o kterém píší staré kroniky, nebylo už po ptáku zdánlivě ani stopy. Většina učenců se tedy přikláněla k názoru, že jménem Kahau byl míněn jiný na ostrovech žijící bouřňák, dnes již také prakticky vyhubený, ale na Bermudách pouze nativní, ne endemický (tj. původní obyvatel, ale vyskytující se také jinde), Audubonův bouřňák, neboli pimlico. Toho názoru byl v dvacátých letech tohoto století i slavný přírodopisec dr. Beebe, který označil Audubonova bouřňáka ve svých spisech jako Kahaua. Nicméně tito učenci se mýlili. Nelze zde dopodrobna sledovat hostorii znovuobjevení ptáka Kahau: Subfosilní zbytky v krápníkových jeskyních, náhodné nálezy, např. původně chybně diagnostikovaný, prý zatoulaný pták z Nového Zeelandu, atd. vedly nakonec k přesvědčení několika nadšenců, že záhadný Kahau přežívá ve zbytcích kdesi na malých ostrůvcích mimo hlavní masu Bermud. |

The history of the Cahows is strange and romantic, much like

the atmosphere and history of Bermuda. When in 1504 the Spanish seafarer Juan de Bermudez discovered the Bermuda islands, there were all manner of seabirds on them in their hundreds and hundreds, thousands and millions. No mammal lived there, the only four-legged life being the original Bermuda lizards or Skinks. The Spaniards discovered and named Bermuda, but did not colonise it. The islands were dangerous to land on - the islands themselves, protrusions above the waterline, and today joined by bridges into one large pair of islands are surrounded by scattered rocks and submerged coral reefs, where many a ship has met its end. Apart from this, during the winter months, by night, the Spaniards were terrorised by the sound of countless wings and wailing cries, which, in those days, must have been audible in a cacophony of ceaseless choirs. For their navigational dangers and mysterious nocturnal wailings the Bermudas were known as "Las Islas del Diablo", the Devil's Islands. Nevertheless, Diego Ramirez, who was driven onto Bermuda's shores by a storm in 1603, discovered that the apparent devils are birds, flying around and crying out at night. These were the Cahows, at that time present over Bermuda in their millions. But already human civilisation began to toll their death-knell, slowly at first. The Spaniards let loose upon the islands hogs as their reserve meat supply in times of need, and the hogs dug out and ate the eggs and fledglings of the Cahows. In those times the Cahows occupied the mainland, where they dug their long corridor burrows in the soft soil. By 1609, when the Sea Venture ran aground off Bermuda while bringing supplies to colonists in Virginia, piloted by Sir George Sommers, the Cahows were to be found only on the outlying islands which the pigs could not reach over the sea. Yet there were still thousands of them. Sommers claimed Bermuda for the British Crown, and out of the wreckage of the Sea Venture his sailors built two smaller ships, the Patience and the Deliverance, which took relief to the hungry colonists in Virginia after all, though Sir George died on the return journey to Bermuda. His body was taken back to England, but his heart was buried in Bermuda, probably less out of sentiment than as a way to ensure that his salted corpse didn't go off on the return journey, heart being euphemistic for entrails. But the Cahows paid a high price for this colonisation, since the colonists found in them an abundant and ready food supply. Apparently it was enough to light a torch on the shoreline at night and club the inquisitive birds to the ground in their thousands. When in 1615 rats came ashore from the ships and destroyed all the food in storage, the Bermudian colonists rowed across to Cooper's Island, and lived on nothing but Cahow meat. In 1616 the governor, Daniel Tucker issued a strident decree "against the spoyle and havocke of the Cahowes", but it came too late. What the people left undestroyed in their wake was finished off by dogs, cats, hogs and rats. So it was, that by the nineteenth century, when the more enlightened naval officers of the Bermuda contingent began to show an interest in that Cahow, cited in the old chronicles, there was no trace left of it, or so it seemed. The majority of scholars took the view that the Cahow was the given name of a different type of petrel living on the islands, nowadays also just about wiped out on the islands, but only a native Bermuda species, not endemic (i.e. an original inhabitant, but also to be found elsewhere), Audubon's Petrel or Pimlico. This view was shared in the 1920s by the famous naturalist Dr William Beebe, whose notes label the Audubon Petrel as the Cahow. Yet these scholars were mistaken. This is not the place to describe in detail the history of how the Cahow was rediscovered: the sub-fossil remains in the stalactite caverns, or the initially mis-classified ostensibly stray visitor from New Zealand etc. all of which led a few enthusiasts to the notion, that the fabled Cahow survives somewhere on the small islets off the Bermuda mainland. |

| Nakonec, v roce 1951, vytáhli američtí

ornithologové L.S.Mowbray a R.C.Murphy z nory na jednom ze skalnatých ostrůvků Kahaua,

sedícího na vejci. Byl s nimi patnáctiletý chlapec David Wingate, který již

předtím, v kajaku, sám pátral po záhadném ptáku Kahau. Wingate pak zasvětil celý

svůj život vlastně záchraně tohoto ptáka. Když byl Kahau objeven v r.1951, bylo na celých Bermudách všeho všudy sedm hnízdících párů. Avšak každý následující rok přišly všechny páry o své jediné mládě. Dokud žili Kahauové na hlavní půdě ostrovů, vyhrabávali si nory sami. Na skalnatých ostrůvcích, kde sídlily jejich zbytky, museli se však spokojit s přirozenými skalními rozsedlinami. A zde se s nimi o hnízdní prostor utkávali právě dlouhoocasí bílí ptáci faetóni, kteří normálně hnízdí v proláklinách a štěrbinách skal. Faetóni hnízdí později než Kahauové. Někdy v březnu přiletěli faetóni, krásní a zdánlivě andělsky nezemští, uklovali k smrti mladého Kahaua a usadili se v hnízdě sami. Byly započaty pokusy o záchranu Kahauů tím, že se do vchodu nory vloží dřevěné víko s otvorem, jenž propustí jen Kahaua, ale ne většího faetóna, leč pro nějaké osobní tahačky a řevnivost mezi zůčastněnými učenci k ničemu konkrétnímu nedošlo a osud Kahauů se zdál nadobro zpečetěn. |

At last, in 1951, two American ornithologists

L.S.Mowbray and R.C.Murphy dragged out of a burrow on one of the rocky islets, a Cahow

found sitting on its egg. With them was a lad of fifteen, David Wingate, who had made his

own exploratory journeys earlier, in a kayak, in search of the mysterious Cahow. Wingate

decided right then and there to devote his life to saving this bird species. When the Cahow was rediscovered in 1951, only seven nesting pairs were found in the whole of Bermuda. Even so, every year thereafter, each pair failed to rear their solitary fledgling. While the Cahows had been living on the mainland, they had dug their own burrows. Out on the rocky islets where their last stragglers survived, they had to make do with natural rock crevices. And it was the long-tailed white phaeton birds who naturally nest in rock crevices and openings who competed with them for these nest-sites. The Tropicbirds nest later than the Cahows. Sometime in March they would arrive, beautiful and angelically ethereal in appearance, peck the young Cahow to death and take over the nest for themselves. Attempts were made to save the Cahows by introducing into the nest mouth a wooden lid with an opening large enough for the Cahow, but not the larger tropicbird, but thanks to some personal disagreements between the scientists involved or whatever, nothing practical came of it and the Cahows fate seemed to be finally sealed. |

the 'Longtail'

| V roce 1957 se však Wingate vrátil ze studií

v Americe, a Kahauů se energicky ujal. Nápad s dřevěnou zábranou se ukázal

správný, bylo však nutno vyzkoušet velikost otvoru. Později začal Wingate pro Kahau

dělat umělé nory z betonu, pro

nedostatek přirozených skalních nor i měkké půdy na ostrůvcích. Populace Kahauů

vzrůstala a vše se zdálo na dobré cestě. Ale v šedesátých letech, vlivem extensivního používání DDT v Americe, začali Kahauové klást vejce s tak tenkými skořápkami, že se bořily dřív, než se z nich kuřata mohla vyklubat a pak hynula. V r.1966 měl Wingate už 21 párů Kahauů, ale jen šest mělo toho roku po kuřeti. Jiní ptáci v Americe trpěli podobně a tak, díky protestům ochránců přírody, počalo se DDT užívat stále méně a méně, až v r.1972 bylo jeho používání zákonem zakázáno. Potom se začalo Kahauům zase dařit lépe a v r.1981 je už Wingate mohl v době páření v noci jasně slyšet až ze svého stanu na Nonsuch. Trvá dost dlouho, než se vzrůst populace projeví také ve vzrůstu počtu nových párů. Pták Kahau totiž potřebuje pět až deset let, než plně dospěje a začne se rozmnožovat. Ale počet vzrůstá. Dnes má Wingate už přes dvě stě Kahauů, ovšem zatím jen dvacet šest hnízdících párů. |

However, in 1957 Wingate returned from his

studies in America, and took charge of the Cahows with great enthusiasm. The idea with the

wooden baffle turned out to be a good one, much as it had to be tried and tested for size.

Later on, Wingate started to make artificial

nesting burrows for the Cahows out of concrete, to make up for the shortage of natural

rock crevices and total absence of soft soil on the islets. The Cahow population grew and

all seemed to be on the mend. But in the sixties, thanks to the extensive usage of DDT in the United States, the Cahows began to lay eggs with such fragile shells, that they used to collapse before the chicks could hatch, thereby causing their deaths. By 1966, Wingate had 21 Cahow pairs, but only six of these had a chick that year. Other birds on the US mainland suffered similar fates and so, thanks to pressure from environmentalists, the usage of DDT reduced steadily, until it was banned by law in 1972. After that, the Cahows had a resurgence and by 1981 Wingate could hear their mating cries clearly at night from his main base on Nonsuch Island. It takes a while for the growth in population to show up in the formation of new pairs. A Cahow needs five to ten years to mature fully and reach reproductive age. The numbers continue to increase. At the time of writing this, Wingate has over two hundred Cahows, albeit only some twenty six nesting pairs. |

| Poslední rána či nebezpečí pro nadšeného ochránce

přírody však nastala letos počátkem roku. Myslím, že se o tom musím zmínit,

protože incident měl širokou publicitu v Anglii a prý také v Kanadě a v Americe a

byl reportéry typickým žurnalistickým způsobem překroucen. Někdy počátkem

letošního roku přivál severák až na Bermudy sněžnou sovu, zřejmě odněkud z

arktické Ameriky. Sova se zařídila na místech, která jí nejvíc připomínala rodnou

tundru, tj. na holých skalnatých ostrůvcích, kde hnízdí Kahauové. Zkrátka a dobře, sněžná sova začala lovit ohrožené ptáky Kahau. Naštěstí se nezmocnila žádného příslušníka hnízdícího páru, protože ti byli právě na své šestinedělní svatební cestě zpátky na moři, ale zato řádila mezi nedospělými ptáky, kteří se v té době vracejí k pevnině a vyhlížejí místa k příštímu hnízdění, třeba až za několik let. Bílá sova seděla na skále a koukala, a hloupě zvědaví mladí Kahauové ji obletovali, co to jako je. Nakonec to sově došlo. Natáhla dráp nad hlavu, nadskočila, a měla oběd. Když David Wingate dorazil na svou pravidelnou inspekci hnízdišť Kahauů, napočítal ke své hrůze mrtvolné zbytky asi pěti ptáků. Po tom, co jsem vám tu o něm pověděl, dovedete si představit Wingatovo zoufalství. Celé noci, v každém počasí, byl venku ve člunu, od ostrůvku k ostrůvku v honbě za sovou. dal vyhlásit, jakou sovu hledá, ve sdělovacích prostředcích a tím si na sebe basadil novináře. Historie honění sovy je zajímavá, ale podrobně jí zde vykládat nemůžeme. Např. americká armáda půjčila Wingatovi odstřelovače, který však sovu asi třikrát netrefil, atd. Nakonec ji zastřelil David sám, brokovnicí, a je teď vycpaná v bermudském přírodopisném museu na Flatts, zatím jen v depositáři. Ale žurnalisté se na Davida sesypali. Nelze se jim divit. Chtějí být živi, k čemuž potřebují co možná nejpikantnější senzace a ornithologií se nezabývají. Zvláště z britských ostrovů vypadala situace jak náleží skandálně. Surový Conservation Officer zastřelil vzácnou sněžnou sovu, aby chránil nějakého domorodého bouřňáka z Bermud. Bouřňáků, totiž běžných, je na britských ostrovech habaděj; zato je tam jen jeden jediný pár sněžných sov na Shetlandách, kde ho ve dne v noci hlídají zase místní přírodní nadšenci. Britská neschopnost vidět věci jinak než z vlastního hlediska se tentokrát obrátila vůči vlastní kolonii a vlastní krvi. Jak to bylo potom v Kanadě a v Americe, nevím přesně, ale nejspíš asi přejali stanovisko britského tisku. Nechtěli pochopit, že sněžná sova je poměrně běžný cirkumpolární druh, výše na sever of Shetlandů nijak vzácný, kdežto Kahauů je toho času dvě stě na celém světě, pouze kolem Bermud, a z toho jich jen asi dvacetšest párů hnízdí a že zmíněný Conservation Officer je třicetiletou obětavou prací doslova vyškrábal hrobníkovi z lopaty. |

The last blow or threat to this committed nature

conservationist came at the beginning of this year. I feel duty-bound to mention it, since

the incident attracted wide publicity in England, and also, I heard, in Canada and the US,

whilst undergoing the usual journalistic distortion. So, sometime at the beginning of the

year, the north wind blew down as far as Bermuda from remote arctic America, one Snowy

Owl. The owl made itself at home in the places that most resembled its native tundra, i.e.

the barren islets where the Cahows nest. To cut a long story short, a Snowy Owl started hunting the endangered Cahows. Fortunately it did not get into its clutches any member of a nesting pair, since these were back out at sea on their six week long nuptial flight, but instead the owl wreaked havoc among the juvenile birds, who are at that time returning to the land to scout for future nest sites, often years in advance. The Snowy Owl sat on a rock and watched the curious young Cahows circling to see what this creature might be. Finally, the owl got the idea. Raise a claw above your head and, voila - lunchtime. When David Wingate came for his regular inspection tour of the Cahow nesting sites, he found, to his horror, the mortal remains of some five birds. After everything I've been telling you, you can imagine Wingate's desperation. He spent night after night, in all weather, patrolling in his boat from island to island in pursuit of the owl. He issued a press release about the owl in question and thus put the journalists on his own trail. The tale of the owl-hunt is fascinating, but we shan't go into details here. Take for instance, that the US government lent Wingate a sharpshooter, who managed to miss the owl on three occasions, etc. In the end David shot it himself, with a shotgun, and it is now a stuffed specimen in the archives of the Bermuda Aquarium and Zoo museum at Flatts Inlet. The journalists came down hard on David. That's not surprising. They need to make a living, to which end they need the most piquant of sensational stories, and their knowledge of ornithology is not great. From the vantage point of The British Isles in particular it looked to be a proper scandal. 'Brutal Conservation Officer shoots rare Snowy Owl to save obscure local Bermudian sea-petrel'. Petrels, of the ordinary sort, are ten-a-penny in the British Isles, but there is only one nesting pair of Snowy Owls up in the Shetlands, guarded round-the-clock by local wildlife enthusiasts. The British, unable to see things other than from their own viewpoint turned against their own this time, their own colony and own blood. I don't know for sure how it went after that in Canada and the US, but they probably replayed it from the British media angle. No-one saw fit to grasp that the Snowy Owl is a common enough circumpolar species, no rarity north of the Shetlands, whereas there are only a couple of hundred Cahows in the whole world, only around Bermuda, and that the aforementioned Conservation Officer had, with thirty years' of painstaking selfless work, literally snatching them off the gravedigger's shovel. |

| Tak tohle je, se vší stručností, historie záhadného

ptáka Kahau, nočního ďábla starých španělských mořeplavců, který je více než

před čtyřmi sty léty strašíval v milionových hejnech, jehož maso zachránilo

anglické kolonisty před smrtí hladem, a ze kterého zbylo v polovině dvacátého

století už jen sedm párů. Jenž byl odsouzen k vyhubení andělsky krásnými ptáky faetóny, do kterých by to nikdo neřekl, a kterého chránil jen jediný věci oddaný a houževnatý učenec. Tuto historii jsem si v duchu opakoval, když jsem na skalnatých, nepřípustných ostrůvcích kolem Bermud s úžasem nahlížel do umělých betonových nor. "Neuvěřitelné se stalo skutkem," splynula mi bezděky se rtů známá hrabalovská fráze. "What did you say?" táže se David. "Oh, nothing, really, a kind of quote," odpovídám. Jen citát, Davide, citát v jazyce, jehož historie se silně podobá historii ptáka Kahau. Taky byl na vymření, taky ho zachránilo pár nepraktických nadšenců a taky ještě nemá vyhráno. A tak jako ty doufáš, že se jednoho dne ptáci Kahau vrátí na půdu vlastních Bermud, tak také my ... ale to bys ty, Davide, potomek mocného, expansivního národa, který obsadil kde co, a jehož jazyk se dnes stal vskutku jediným opravdu mezinárodním jazykem, to bys ty asi nepochopil. Nyní jsem se již vrátil, a píšu tím divokým, Kahauovským jazykem o svých zkušenostech. A skoro bych už sám nevěřil tomu, co jsem zažil. Ale mám důkaz. Péro z ptáka Kahau, které mi David Wingate slavnostně věnoval, ve futrálu od brejlí. |

So there you have it, with all due brevity, the history of

the fabled Cahow-bird, the nocturnal devil, scaring Spanish mariners over four hundred

years ago in its multi-million flocks, whose meat saved the English colonists from

starvation, reduced to only seven pairs by the middle of the twentieth century. Which was sentenced to death by tropicbirds so angelically beautiful nobody would have thought them capable of such things; and which had only one devoted and indefatigable scientist for its protection. This was the tale I repeated to myself under my breath when looking with awe into the man-made, concrete nesting burrows strewn across rocky and inaccessible islets around Bermuda. Inadvertently a phrase by Bohumil Hrabal slipped from my lips ("Neuvěřitelné se stalo skutkem" - The Incredible has come to pass.) "What did you say?" asks David. "Oh, nothing, really, a kind of quote," I reply. A quote, David, in a language whose own history strongly resembles that of the Cahow. Driven almost to extinction, then saved by a few impractical enthusiasts, and not fully out of the woods yet. And, just as you hope that one day the Cahows will return to the Bermuda mainland, we too hope ... but you, David, descended from a powerful, expansive nation, which colonised practically everything going, whose language is today the only truly international means of communication, you might find that notion a little fanciful. Now I am back, writing in this wild, Cahow-like language about my experiences. And I could almost begin to doubt I ever lived through it at all. But I have proof. The Cahow feather I was given by David Wingate with all due ceremony, in my spectacle-case. translated by VZJ Pinkava |

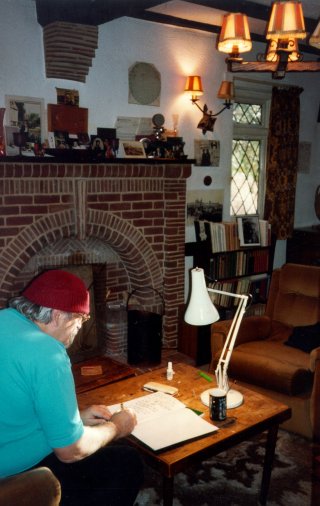

the author in his study